A New Priest Negotiating the Transition

May 2005

Nonoy is the Bikol term used by parents or elders to call their sons, nephews or grandsons, or any young boy. Its variations are Noy, Nonố or simply Nố. It carries feelings of tenderness and affection. If anyone among your friends has any of these nicknames, most probably he is a Bikolano or has Bikolano roots. You can be sure of that in the same way that Utoy most likely hails from either Quezon or Batangas. Dudong, on the other hand, must be a boy from the Visayas or Mindanao.

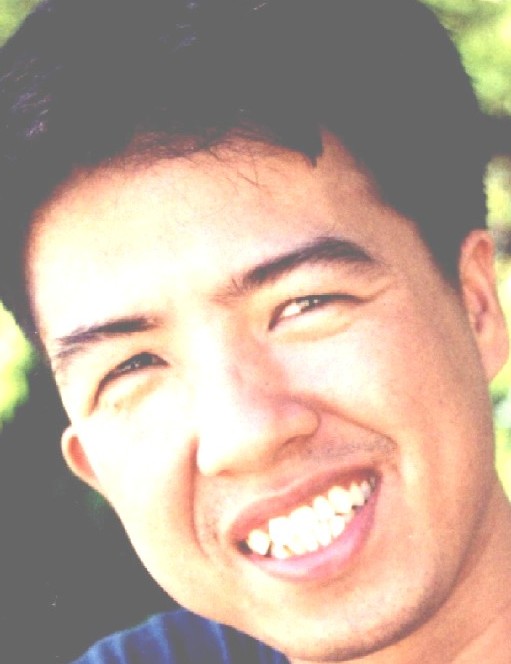

My parents and my grandparents call me Nonoy. My younger siblings call me Nonong Norlan. Being called Nonoy always gave me a sense of being loved most sincerely by the parents, uncles and aunties. It always made me conscious of my status in the family as the younger member, and therefore, as standing below my parents and grandparents in the family hierarchy. I defer to their will and wishes. I obey their orders and commands. I bow to their authority.

Things changed, however, after I was ordained priest. In Bicol where culture and religion are interwoven to each other, priests are held in high esteem. In the towns or cities where they are serve, they command great respect, very much like or even greater than the municipal mayor or provincial governor. People seek their advice and counsel in their personal and family problems. Parishioners follow the directives and policies formulated by the priest. Even those older than him in age and experience take his hand to kiss them.

Hence, when I returned to my parents’ hometowns of Magarao and Calabanga, both in Camarines Sur, my grandparents and relatives, all of them older than myself, came to me, their faces beaming with joy, and took my hand and kissed it, making mano po to me. I felt awkward in that situation: my lolo and lola, my uncles and aunties, whom I hold in high esteem and regard with deep respect, making mano to me! Shouldn’t I be the one making mano to them? Not knowing how to react in such situation, I also took their hands and made mano po to them, at which one of my aunties said, “Kami na ang ma-bisa saimo ta padi ka na. Father Norlan ka na!” (We should be the ones kissing your hand because you are now a priest. You are now Father Norlan!)

In the two weeks that I stayed in Bicol, visiting my relatives, making small talks with them, catching up with the latest news about this or that relative, no longer was I called Noy or Nố as often as before I was ordained. They would address me as Father Norlan. Then I slowly realize that something has indeed changed since ordination day. Yes, I say, to myself, I am the same person as the day before I was ordained, but to the people who witnessed the ordination, and those who attended my thanksgiving mass, there is a new person standing in front of them. This new priest is no longer just the Noy or Nố whom they asked to do errands or whom they reprimanded for a naughty act when he was still a young boy.

One day, one of my aunties approached to me and shared with me her problems at home, with her children, with her siblings and with her job. I was so surprised I did not know what to say in response to her sharing. These were stories she would never tell me before because some of them involved my parents or my other aunties whom I also respect. It was not a confession, but I thought what she shared were confessional matters. Then again, I heard the statement that explained why all these were happening: “Sinasabi ko ni saimo ta padi ka na. Ano masasabi mo, padi?” (I’m sharing these with you because you are now a priest. What can you say, Father?)

On my way back to Manila, while on the bus, I was trying to make sense of the experiences since my ordination, particularly those that happened in my parents’ hometowns. I recalled how easy it was for me to be vested in my priestly garments of chasuble and stole on my ordination day. How could it not be done easily when there were six people assisting in the investiture! But how difficult it is, I thought, to put on the true priestly vestments: not those made of silk or satin, but those invisible albs and chasubles which people see in me which draw them to me, which makes them take my hand and kiss it.

Are these invisible vestments their expectations of a priest? their perceptions? their projections? Or could it be what our theology books call the “Christ-in-the-priest”? That in their priests, people see, not the priest, but Christ who makes use of the priest as His instrument that He may be tangibly present among His people as their Head? Is it Christ who exercises authority and power over them whom they acknowledge as they take my hands to kiss them? Is it Christ who listens to their every affliction who, they trust, can ease their sorrows and burden? Is it Christ who gives his body and blood, His whole self, whom they recognize as their Lord and Saviour?

The transition that I am undergoing: from being a son, Noy or Nố, to being a father, Father Norlan, has been accompanied by amazement at how the sacramental principle works: how the Lord can make use of tangible, lowly and fragile earthly instruments to manifest His all-powerful, albeit invisible, presence in the world. The psalmist says: “My sin is always before me.” This, indeed, is my experience before the mysterious workings of God through the sacraments. Before the body and blood Christ, made present on the altar by the power of the Holy Spirit upon the gestures of my hands and words of my mouth, I confess my unworthiness to be the instrument of the transformation of the bread and wine. And as I raise the bread and wine in the climactic doxology to the Father, I meet the eyes of the people, all eager to receive the gifts of Jesus’ body and blood. Then, I begin to understand what it means to be called “Father Norlan.”

The transition from being “son to father” can not be undertaken apart from the community of believers. It is not a philosophical or theological question that can be discussed and resolved in a classroom. It is a task that can not be performed in a carpeted private chapel or in the priest’s airconditioned bedroom. It is a journey that has to take place where the people of God are: whether in the Sunday Eucharist or in a First Friday reconciliation service; both in the canonical interview for marriage and in the burial of a one-month old baby; in the picket line of workers on strike as much as in the cancer or psychiatric ward of a government hospital.

The priest is a son who has been made, or precisely, is being made (present progressive tense!), into a father, to be for his community, the father that welcomes the prodigal son back into his arms, into his love, even as the priest always remains a son who needs to constantly return to the Father who assures the priest/son-father: “You are my son! Today I have begotten you!”

Monday, May 02, 2005

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment